“10 out of 10 would rather be playing Fortnite right now…”

Meditation, now a billion dollar industry, seems to be one of those things that everyone agrees that they should do, but maybe without really understanding why: one of those “it’s gotta be good for ya” sorts of things. That’s always a bit of a red flag for me. Kinda like yoga, or vegan organic dog soap *brow raise*.

But hey, maybe I’m just cynical. Embittered by years in the fitness industry trenches, weathering onslaughts of wellness shakes and saran-wrapped ponzi schemes. It makes a man salty after a while.

So, I’m trying to give meditation a solid chance, hence this review of the literature.

Evidently, there are many kinds of meditation, but the most thoroughly studied and probably the most effective form is known as “mindfulness” meditation. One study gave the following apt description of mindfulness:

“The current acceptance of what a mindful path is, refers to a psychological quality that involves bringing one’s complete attention to present experience on a moment-to-moment basis, in a particular way: in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.”

Alleged benefits of this kind of meditation include disease prevention, decreased stress, pain, anxiety, and blood pressure and improved cognitive performance. Surveys have shown that most people who meditate do so for general wellness and disease prevention, as well as improving energy, memory and concentration.(1)

The questions I was eager to answer with this article were:

- Does mindfulness meditation actually yield these benefits? If so, how much?

- If not, does it do anything else that’s cool?

- How do these effects compare to other means to the same ends, such as exercise? In other words, is meditation actually worth doing, or should you do something else instead?

After ploughing through dozens of studies on these topics, one thing seems abundantly clear: More research needs to be done before drawing hard-lined conclusions about meditation.(2) Many large-scale analyses of the literature have emphasized the prevalence of poor study design, high probability of bias in the studies, the lack of consensus in the literature on many topics and the inherent difficulty of studying meditation objectively. With that in mind though, there are some pretty interesting trends that stood out to me:

1. Mediation does seem to be moderately effective in reducing pain. This effect also seems to increase as people become more proficient meditators. The effect remains when compared to placebo:

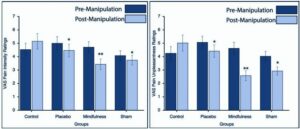

This study used a placebo cream applied to the painful area and compared the effects to those of mindfulness meditation and “sham” meditation (“sham” meditation was essentially non-directed meditation that allowed any kind of thinking).

As you can see, mindfulness did have a slightly greater effect than “sham” and placebo.

Brain scans indicated as well that the neural process by which meditation decreases pain seems to be different than the process by which placebos decrease pain.(3)

Interestingly, a meta-analysis focusing specifically on various kinds of headaches, including migraines, showed promising results for pain management there as well (4).

2. General wellness/ disease prevention (blood pressure, stress, anxiety): General wellness and disease prevention is the main reason people reported practicing meditation. In the literature, this seem to encompass generally stress, anxiety, blood pressure and other risk factors for heart disease:

-

Stress & Anxiety: Many studies agree that meditation can be an effective way to decrease stress and anxiety, although it is probably less effective than other commonly prescribed methods. Exercise, for example, even when light, is probably better for psychological well-being and stress relief than meditation. (5)(6)

-

Blood Pressure, BMI & Heart Disease: Heart disease is still the leading cause of death in America, so cost effective methods of prevention are of course very much worth paying attention to. Research does seem to support the efficacy of meditation for decreasing blood pressure and improving other risk factors for heart disease, but again, not very substantially and generally less than other common interventions such as exercise.(7)(8)(9)

0 Comments

Leave A Comment