As we’re all painfully aware, there’s no shortage of over eager insta-experts and unwelcome gym pundits in stringers, quickly dishing out half-baked lifting advice as if with large, sloppy spatulas. These are some common cues you’ve probably heard (probably with some quiet but appropriate confusion), why they kinda suck and how we can do better, according to science and common sense.

1.“Squat through your heels” Try this: sit down on your couch, plant only your heels on the ground and try to stand up and sit back down without letting the front half of your foot touch the ground. If you didn’t fall on your ass, good job. You’re not the only one that feels awkward and weak doing that. It’s no wonder people struggle with balance when trying to “push through their heels” with several hundred pounds on their back. I understand that this cue probably originated from coaches trying to get their athletes to keep their heels from popping up off the floor when they squat, because squatting on your toes isn’t great either, but pushing through the heels just reverses the problem and doesn’t effectively teach us how to maintain a solid base. Instead, try this:

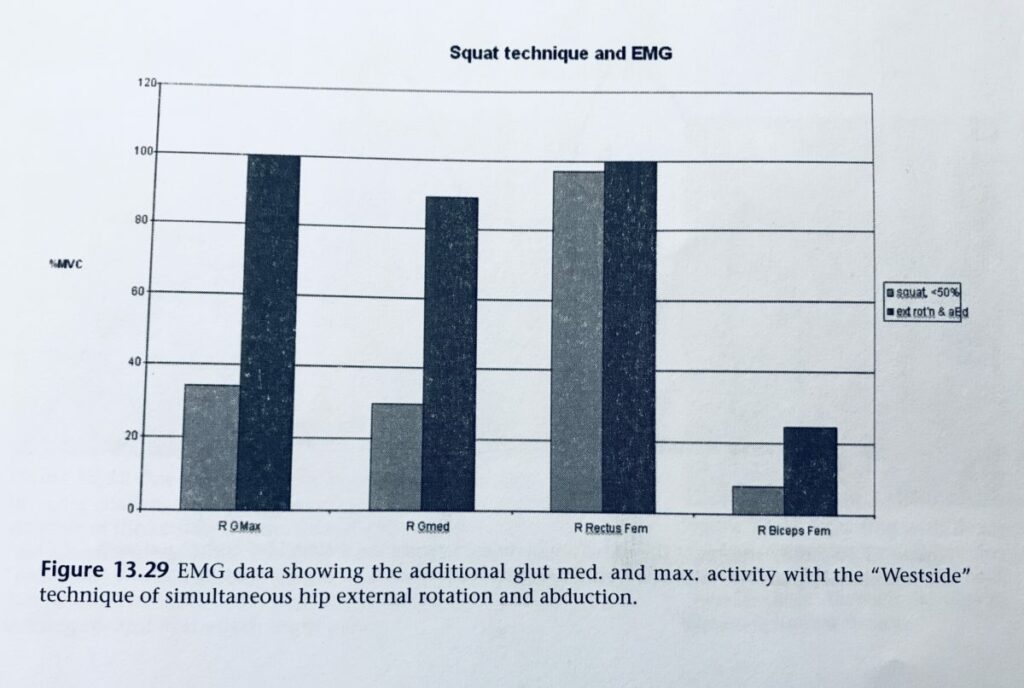

Spread the floor. Grip the floor with your entire foot and without moving your feet, push outward as if trying to rip the floor open between your legs. Maintain this tension throughout the entire squat. This method very often solves people’s balance issues in the squat and improves their bar path. It also substantially increases contractile force in the hamstrings and glutes, as shown in this study by Dr. Stuart McGill (Black columns show muscle activation with this method, grey columns without (1)).  You can try it right now without weight, and you should feel some engagement in your glutes and hams immediately if you’re doing it correctly. Make sure you’re wearing shoes that give you solid contact with the flat surface you’re squatting on. Running shoes with a stiff curve in the sole are as bad for squatting as squat shoes are for running.

You can try it right now without weight, and you should feel some engagement in your glutes and hams immediately if you’re doing it correctly. Make sure you’re wearing shoes that give you solid contact with the flat surface you’re squatting on. Running shoes with a stiff curve in the sole are as bad for squatting as squat shoes are for running.

2. “Lift with your legs, not your back” Lifting with your legs is great, but your back is packed with big muscles for a reason. It’s not bad if you “feel it in your back”. Yes, back muscles are largely stabilizers and are generally set up to stabilize the spine rather than generate power, BUT this cue has noobs terrified of bending over for anything. The muscles in your back (which is part of your core, btw) should be contracting to maintain a neutral spine, and your glutes, hamstrings and quads should be contracting to bring the hips forward. “Lifting with the legs” often has people trying to squat everything up off the floor and doesn’t allow them to effectively use the muscles in their rear. Instead, do this:

“hip hinge” Stick your butt back! (Caveat: this is not a squat cue, it’s a cue for picking things up off the floor properly). If you squat excessively to pick something up off the floor, your knees are going to get in the way, you’re going to have to reach out in front of them to grip the item and you’ll probably feel weak and awkward. To get your knees out of the way, stick your butt back and bend over with a flat back.

3. “Inhale down, exhale up” This is acceptable for smaller lifts that don’t require much core stability, but it’s utility ends there, as it doesn’t allow for maximal core bracing or substantial intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). For larger, compound movements like the squat, deadlift, clean, snatch etc. greater core stability is essential for both safety and better performance. Instead, do this:

Inhale, brace, complete the lift, exhale. Think of your core musculature as the walls of a tire. You can load up and lift with a flat tire that leaks air under pressure, or you can inflate the tire to keep it solid and responsive under load. A solid tire allows for greater force production and greater spinal stability. To brace properly, take a big breath into your belly and, while holding that breath, brace your core hard, as if you are about to be punched in the gut. This substantially increases intra-abdominal pressure and spinal stability (2). A good cue is to think of your core as a cylinder that you will fill with air and then crush from top to bottom. Again, this sort of bracing is for heavy, compound movements requiring substantial core stability, not aerobics or accessory movements targeting small muscle groups.

4. “Knees behind the toes!” In another case of poorly interpreted science, it has become popular to insist that the knees must always stay behind the toes throughout the entire squat, due to higher shear forces in the knee at the deepest part of the squat, where the knees travel past the toes. Shear forces are in fact higher there, but still moderate. The necessary extreme specificity of such studies leaves the hasty reader blind to the practical implications of squatting this way. Keeping the knees behind the toes often causes lifters to groove faulty movement patterns by forcing them to excessively stick the hips back in descent and raise the hips in ascension, preventing optimal use of the quads and preventing a more upright torso (3). Instead, do this:

Hips and knees break at the same time. Instead of sticking your hips way back to avoid forward knee travel, allow your hips and knees to bend at the same time, thereby distributing torque evenly between the hips and knees.

5. “Belly button to spine!” Somehow this one has crept into the lifting world, probably via Pilates and Yoga instructors. It is common for an instructor to have students “pull the belly button to the spine” in order to “activate the core.” This has been thoroughly debunked though, in another study by Dr. Stuart McGill, showing that this cue actually decreases core stability substantially (4). While it may be a harmless cue while lying flat on a mat, it should certainly not be used while lifting heavy weight.

Instead, refer back to 3.a.

As always, I hope this was helpful for all of you! Let me know if you have questions about any of these or about any other cues or tips you’re curious about.

Sources:

- McGill, Stuart. “13.” Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance, Backfitpro Inc., 2017, pp. 254–256.

- Cholewicki, Jacek. “Intra-Abdominal Pressure Mechanism for Stabilizing the Lumbar Spine.” Journal of Biomechanics, Elsevier, 24 Aug. 2000, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021929098001298.

- Fry, Andrew C. “Effect of Knee Position on Hip and Knee Torques During A Barbell Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2003, luciano.si/images/blog015_raziskava.pdf.

- Grenier, Sylvain G.; McGill, Stuart; “Quantification of Lumbar Stability by Using 2 Different Abdominal Activation Strategies.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Volume 88 , Issue 1 , 54 – 62.

0 Comments

Leave A Comment