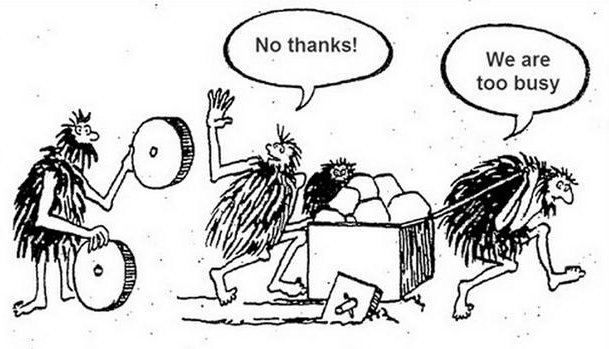

Whatever your athletic goals are, training for them without learning a bit about what makes a good training program is kinda like walking 20 miles to the grocery store because you’re too lazy to put gas in your car (not smart). I’m glad you’re getting exercise, but you should know that smart people have figured out faster ways to get to grocery stores, and the same is true of your athletic goals. Wheels aren’t complicated, but it did take 300,000+ years to invent them, so let’s not do that again.

A training program, for those who don’t know, is simply how you select and arrange your exercises over time in order to achieve your goal. The details will depend on the individual and the goal, but the following three things should be accounted for in every training program. If they aren’t, your program probably sucks.

First though, let’s establish some primordial basics. Practically everything essential to a training program can be deduced from the following sentence:

All physiological adaptations are biological responses to a new environment.

That means:

-The point of adapting is to handle the new “environment”, i.e. new stress. Therefore your adaptation will be specific to the stress applied. Practically speaking, in order to get better at running, you’re gonna need to do some running. Specificity is king. Stop stressing minutia and weird new exercises with 6 bands and 2 chains on a bosu ball with a cone on your head or whatever. Stop doing new exercises every time you go to the gym. Prioritize what you’ve decided you want to get good at.

-If the stress isn’t new, there’s no point in adapting, because you can already handle it. That means that in order to continue progressing, you must continually add new stress. So, if you run one mile everyday for ten years, you’re never going to wake up and be able to run 20 miles. Instead, you’ll need to do something like 1 mile, then 1.5, then 2… all the way to 20 and beyond. That’s called Progressive Overload. Keep careful track of what you’re doing so that you can incrementally increase the load.

-New stress is damaging by definition. Too much damage without the opportunity or resources to recover will simply remain as “damage”. So we can reasonably infer that if you run 40 miles every day without ever sleeping or eating, you won’t adapt, you’ll simply degrade. Training stress should therefore be arranged with respect to your capacity to optimally recover and adapt. That capacity is known as SRA Curve (stimulus, recovery, adaptation). That means don’t deadlift heavy every day for 3 weeks and then stop for 3 weeks. You would make much better progress if you deadlifted one or two times a week for 6 weeks.

“But can’t I just go work out and get OK results without worrying about all this sciencey stuff??”

Well, something is probably better than nothing. But respecting these principles can literally save you years. One of my biggest regrets as an athlete is that I didn’t use any kind of program for 7 years. I figured that if my training felt hard enough I was probably doing it right. Turns out that’s nonsense. I did become more fit than the average Joe over time, but as the years went by I grew increasingly frustrated with my lack of progress. I finally tried some bastardized version of “5×5” and made more progress in the following 2 years than I did throughout my first 7. A good training program isn’t a magic pill. Progress still takes tons of work and time. Let’s not make it harder and slower than it needs to be.

As always, I hope this was helpful for you guys! Message me if you’re curious about programming or any part of this article. I’m always stoked to talk to anyone interested about it!

1 Comment

Leave A Comment